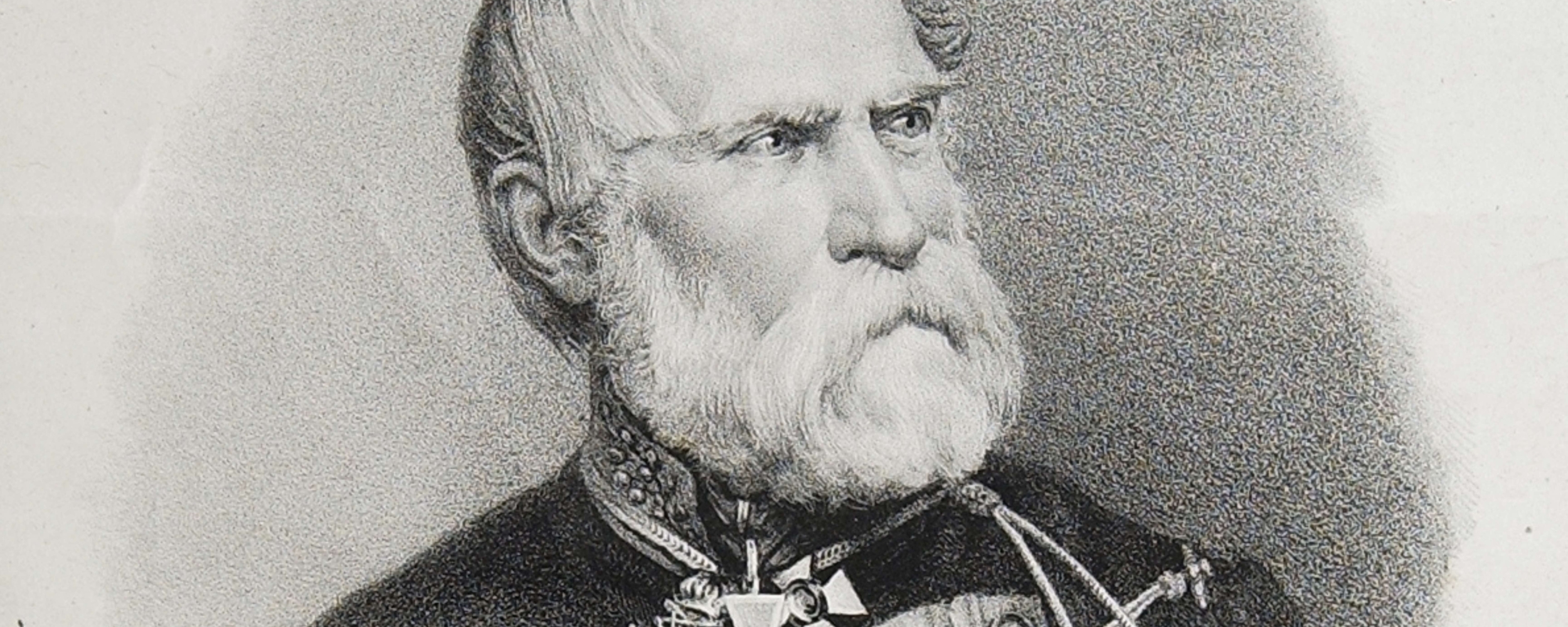

Siebold

Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), collector in Japan

Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold was born in the city of Würzburg in Bavaria (Germany), into a family of physicians. His grandfather, father and both his uncles were professors of medicine at the University of Würzburg. It was at this same university that Siebold began studying medicine in 1815.

In 1822 Siebold entered the service of the Dutch East Indies Army as chief medical officer stationed in Batavia. There he caught the attention of the Governor-General who thought him to be the ideal person to send to Japan, a country that was destined to play a central role in the rapidly changing world politics. Until then, Japan was an unknown power with strictly closed borders. Trade was only allowed through the Dutch trading post at Deshima, a small artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki.

In 1823 Siebold arrived in Deshima, his assignment was to collect information on the islands of Japan and its social and political structures and to explore the possibilities of expanding the existing trade. Foreigners were not permitted to leave the trading post however, as a physician Siebold found ways to circumspect this regulation. After Siebold had cured a prominent government official he was given permission to open a small practice outside the trading post and make house calls on Japanese patients.

During his first visit to the Japanese mainland, he contacted Japanese doctors and scientists. Some of whom had already learned how to speak and write in Dutch and were known as Rangakusha – literally: Holland experts. Japanese officials had encouraged the learning of Dutch among a small group of scientists to understand the books and maps the Dutch brought with them as gifts. Siebold's house soon became a meeting place for lectures, and discussions and Siebold himself was regarded as an expert on Western science. Through these contacts, Dutch became a Lingua Franca, providing Japan access to Western science and inventions.

Siebold also won acclaim as a general practitioner and made frequent house calls in the area surrounding the trading post. He was not allowed to receive payment for his services so grateful patients often gave him gifts instead. These gifts formed the basis of his ethnographic collection. Following the examples of Jan Cock Blomhoff (1779-1853), Commandant of Deshima between 1818 and 1823, and of bookkeeper Johannes van Overmeer Fisscher (1800-1848), Siebold collected many everyday household goods, woodblock prints, tools and handcrafted objects.

He concentrated on collecting plants, seeds, animals, and a variety of everyday utensils. Siebold hired local artists to record images of animals, objects and daily life on paper and paid three professional hunters to hunt down rare animals. During his trips to patients, he collected as much natural material as he could and his students brought him whatever they could lay their hands on.

In 1825 two assistants from Batavia were assigned to Siebold: apothecary Heinrich Bürger and the skilled painter C.H. de Villeneuve. Bürger played a vital role in collecting objects and in 1828, after Siebold was no longer allowed to practice, became his successor.

In 1828 Siebold made the court journey, the so-called Edo Sanpu from Nagasaki to Edo (present-day Tokyo) and was to leave for Java, immediately after his return to Deshima. During the lengthy court journey, Siebold not only collected many plants, animals and artifacts, but also came into possession of maps of Japan. The maps were discovered by the Japanese authorities and Siebold was subsequently accused of high treason and spying for Russia. The possession of maps was strictly forbidden. In 1829, after a period of house arrest during which many of his contacts were investigated, Siebold was expelled from Japan in 1829 and forbidden to return. At that moment Siebold could not know that this ban would be lifted in the years to come.

Up to then his collection had been kept in several cities, spread over institutes in Leiden and the Belgian cities of Ghent, Brussels and Antwerp. After a brief stay with his family, Siebold moved to Leiden and settled in a canal house on Rapenburg 19. The house was on the same canal as the botanical gardens and opposite the museum of Natural History (today located elsewhere in the city of Leiden). As early as 1831 Siebold’s collection was opened to the public. After displaying it at several locations in Leiden, Siebold opened a museum in his Rapenburg home in 1837.

The natural history materials had come to Leiden in four shipments, sent during Siebold's stay at Deshima. The last shipment he accompanied himself when he was forced to leave Japan in 1829. Heinrich Bürger remained on Deshima and managed to send three more shipments in the following years. These shipments, with more than 10,000 items in total, form the Japanese collections in museum Naturalis and the National Herbarium in Leiden.

Thanks to the vast number of animals Bürger and Siebold had sent to the Netherlands, zoologists Temminck (Coenraad Jacob, 1778-1858), Schlegel (Hermann, 1804-1884) and De Haan (Wilhelm, 1801-1855) were able to document a full description of Japanese fauna. Their research was published in 'Fauna Japonica' between 1833 and 1850 and the Japanese animal world, unknown in the West until then, became the best-documented fauna of all non-European countries. King William I expressed a strong interest in Siebold's collection and after some urgings, the Royal cabinet of Rarities, (het Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden) was finally formed combining the Siebold collection and that of two other important researchers at Deshima. Siebold’s collection was bought by the Dutch government and the new museum became the predecessor of the current Wereldmuseum Leiden.

In the years that followed, Siebold acted as an important advisor on Japanese matters for various countries. In 1859 he travelled to Japan one last time.